That was the time when the Indian automotive industry was getting on to its feet and learning to walk, with two young companies — then called Hero Honda Motorcycles and Maruti Udyog — joining the club of Tata Motors (CV), Ashok Leyland, Mahindra & Mahindra, Premier Automobiles, Bajaj Auto and Hindustan Motors.

Maruti Udyog in was born under the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s vision of bringing a people’s car to India, with her son Sanjay becoming its first managing director. Over the next few years, Sanjay Gandhi worked hard to build an ecosystem and made some industrialists join the mission, which accelerated the development of a local component industry.

Sanjay Gandhi had approached Germany’s Volkswagen and Suzuki Motor of Japan for a possible collaboration to start manufacturing cars locally. Since then everything is history — Maruti Suzuki, as the company is now known, accounts for about half the passenger vehicles sold in this country today.

He also approached Lalit Suri, who later became instrumental in setting up probably India’s first automobile air-condition manufacturing firm, Subros. It was set up in 1985 as a joint venture among the Suri family, Japan’s Denso Corp and Suzuki Motors.

In the two-wheeler space, Rico Auto and Munjal Showa joined the bandwagon with Hero Honda, the JV between India’s Hero Group and Japan’s Honda Motor. Now, after a decade of their split, the former JV partners are the No.1 and No.2 two-wheeler makers in India.

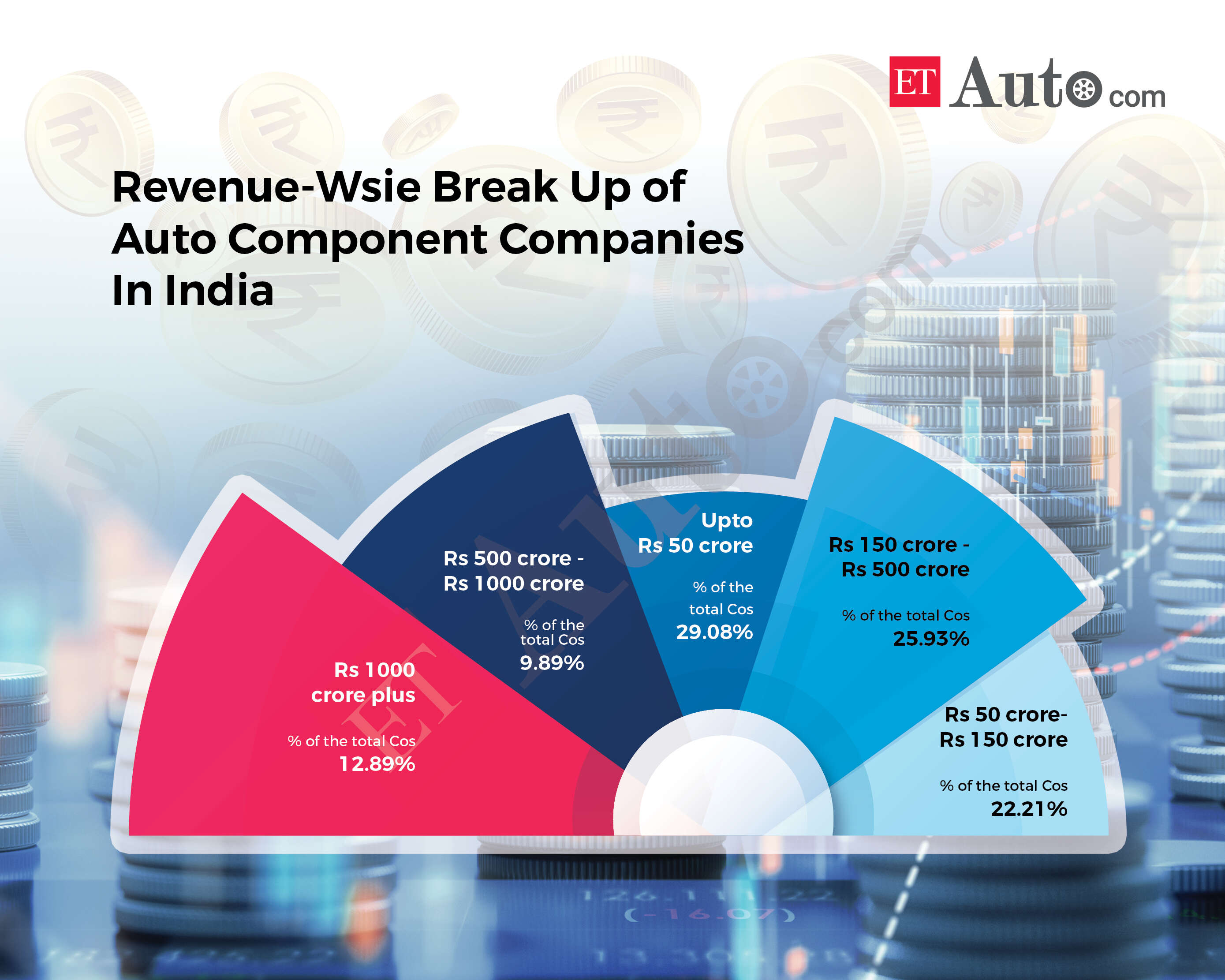

Over the years, the Indian auto-component industry grew at least as fast as the vehicle manufactures. In the country’s $104 billion revenue automobile industry, component makers account for more than half at $57 billion. The story isn’t that impressive when looked closely into, at least on an Indian perspective.

Who Really Owns It?

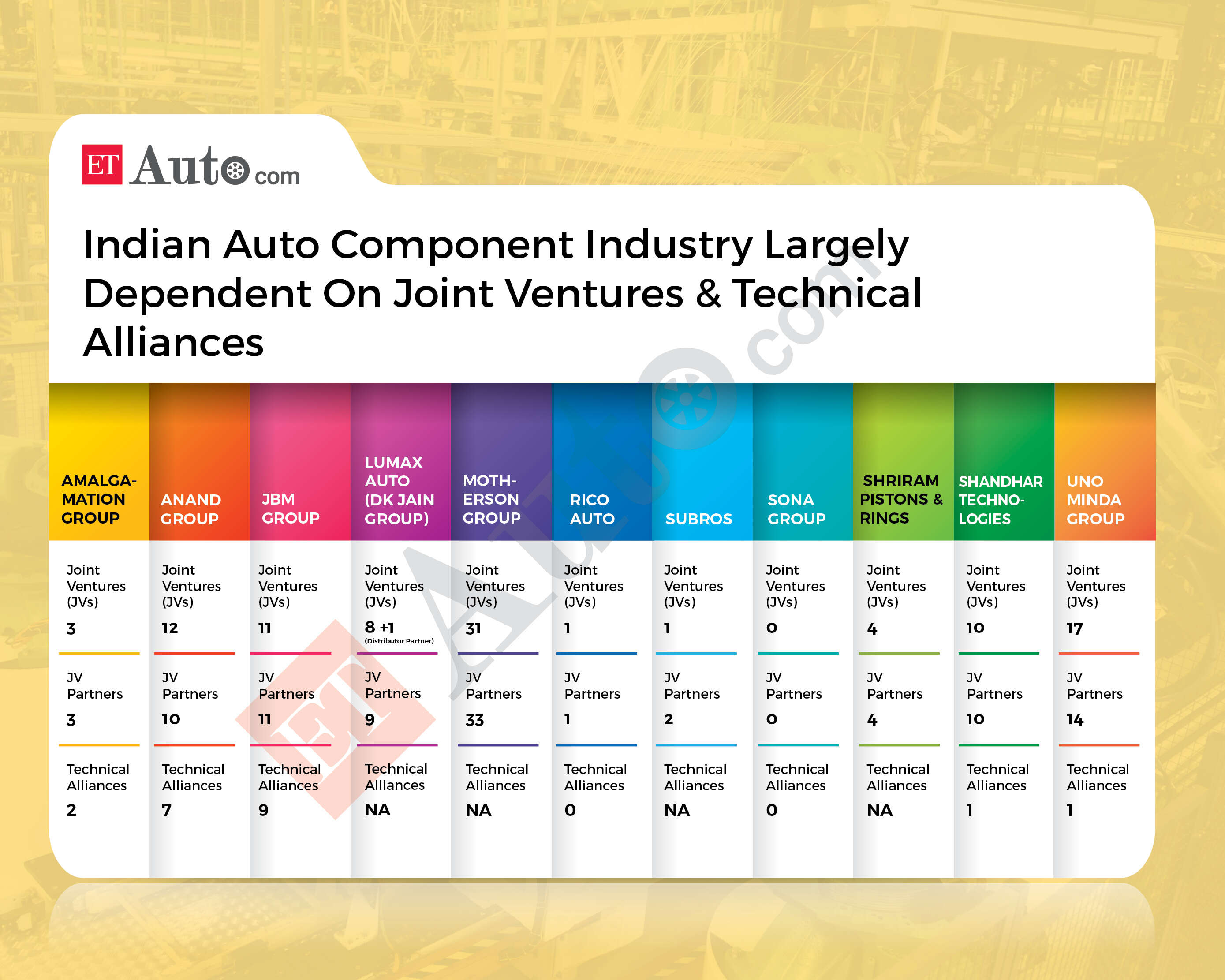

A large number of Indian component makers are heavily dependent on foreign companies to get technology and either are working with them as joint venture partners or have formed technical alliances.

“Traditionally, most of the Indian component makers did not focus on in-house R&D. For every new technology they have looked at their partners. Some component makers have collaboration running into huge numbers,” said IV Rao, an industry veteran and one of the architects of Maruti Suzuki’s research and development programme. “However, some of the Indian manufacturers are taking baby steps in this direction,” he added.

Interestingly some of the international companies, like Bosch, BorgWarner, Denso and Magneti Marelli have been developing technology locally in India.

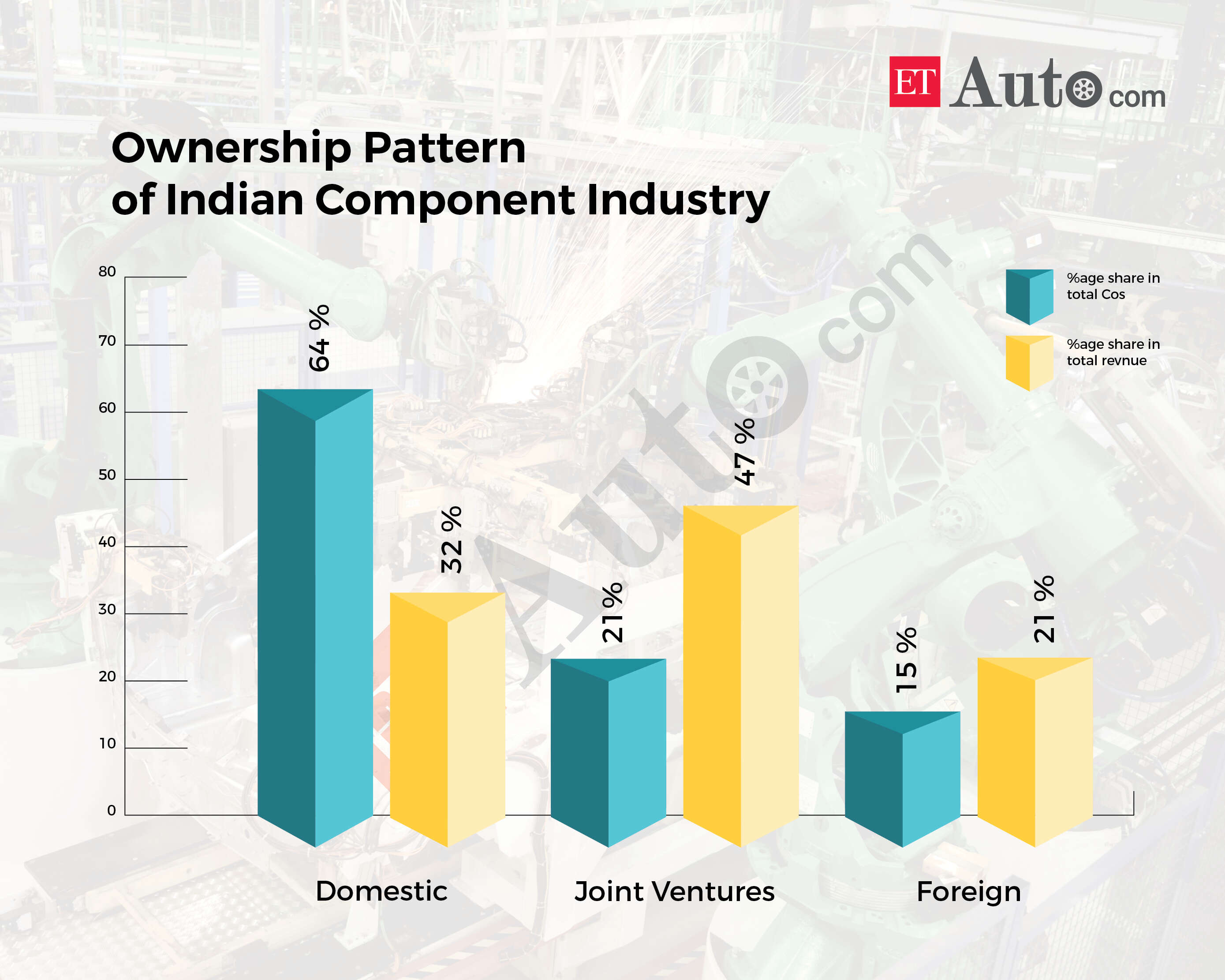

According to our analysis, 64% of total component companies in fiscal 2018 were solely owned by Indian business houses, but they contributed only 32% to the industry’s revenue. Remaining 36% of the companies were either JVs or foreign-owned, and they accounted for 68% of the revenue. Many of the homegrown companies also have technical alliances with foreign firms.

What Created This Situation?

There is a declared strategy in the Indian automotive industry to follow Europe, even on emission standards, said Rao. So, we have never been able to create independent innovation here.

“Since most of the vehicles are designed and developed overseas and their local suppliers work with them, so when they come to India, they ask Indian manufacturer to collaborate with them to bring that technology in a shorter time. That the reason JVs and TAs (technical alliances) become instrumental,” Rao said.

Apparently, even though India has been recognised as the global manufacturing hub for small cars, only a very minuscule number of cars are completely designed and developed here. One product that we could recall of being locally developed in the last few years is Maruti Vitara Brezza.

Automotive Component Manufacturers Association president Deepak Jain, however, defended the current arrangements in the industry, saying that it was still at a nascent stage.

“The first two decades were spent on learning the manufacturing technique, but now the industry is moving towards R&D, too,” he said, adding that India’s focus was only on designing and there was hardly any research and development.

Indian parts makers on average still spend less than 1% of their revenue on R&D, even as these JVs and technical alliances come at a huge cost. The deals often weigh heavily on the profitability of the Indian companies as they have to share the profits or pay a royalty.

These also bar many domestic companies from accessing global markets, as the foreign companies most often have a different JV partner or subsidiaries in those countries.

However — though not very often — it works in the reverse direction, too.

“There are multiple reasons for joining a JV, but the main reason is to get technology and also some customer base. You also get the opportunity to supply back to the JV partner in overseas markets,” Sona Group chairman Sunjay Kapur said.

The Sona Group had started with a forging company in collaboration with the Mitsubishi Group and then went on to have a joint venture with Koyo of Japan to manufacture steering systems. Eventually, after developing adequate in-house technology, it ended both the JVs.

There would also be other reasons to exit partnerships. Recently, the Rs 10,000-crore Anand Group ended an almost three-decade-old joint venture with Federal Mogul, after the latter was acquired by Tenneco Inc. Tenneco was competing with the Indian company in some international markets. The Anand Group still has 12 JVs and seven technical alliances.

Auto-parts makers shell out as much as 5 percent of their revenue towards royalty.~

In another instance, a few years ago, American firm BorgWarner split with the Vikas Group and started a fully owned subsidiary in India.

According to Uno Minda Group chairman NK Minda, the contribution of overseas design and development is the highest in passenger vehicles, while local development is higher in case of two-wheelers and commercial vehicles. His company pays about 2% of its revenue as royalty and has a total of 17 joint ventures.

If this is the situation at the supplier side, it is skewed in favour of foreign-owned companies among automakers too.

The contribution of Indian-owned manufacturers (primarily Tata Motors and Mahindra & Mahindra) in passenger vehicles has contracted to about 12.3 percent of domestic sales in FY2020 (year-to-date) from more than 23 percent in FY19. In two-wheelers and commercial vehicles, Indian-owned manufacturers (Hero MotoCorp, TVS Motor, Bajaj Auto, Tata Motors, Ashok Leyland, etc.) continue to hold the lion’s share.

Notably, the auto and ancillary sectors top the list of industries in terms of the royalty payout. According to government data, royalty paid to foreign entities increased to Rs 27,000 crore (about $4 billion) in fiscal 2018 (across all industries) from Rs 22,728 crore in the previous financial year.

Auto-parts makers shell out as much as 5 percent of their revenue towards royalty, almost similar to in pharma, which is another sector driven by patents. The royalty is majorly towards manufacturing technology and high-precision technology components.

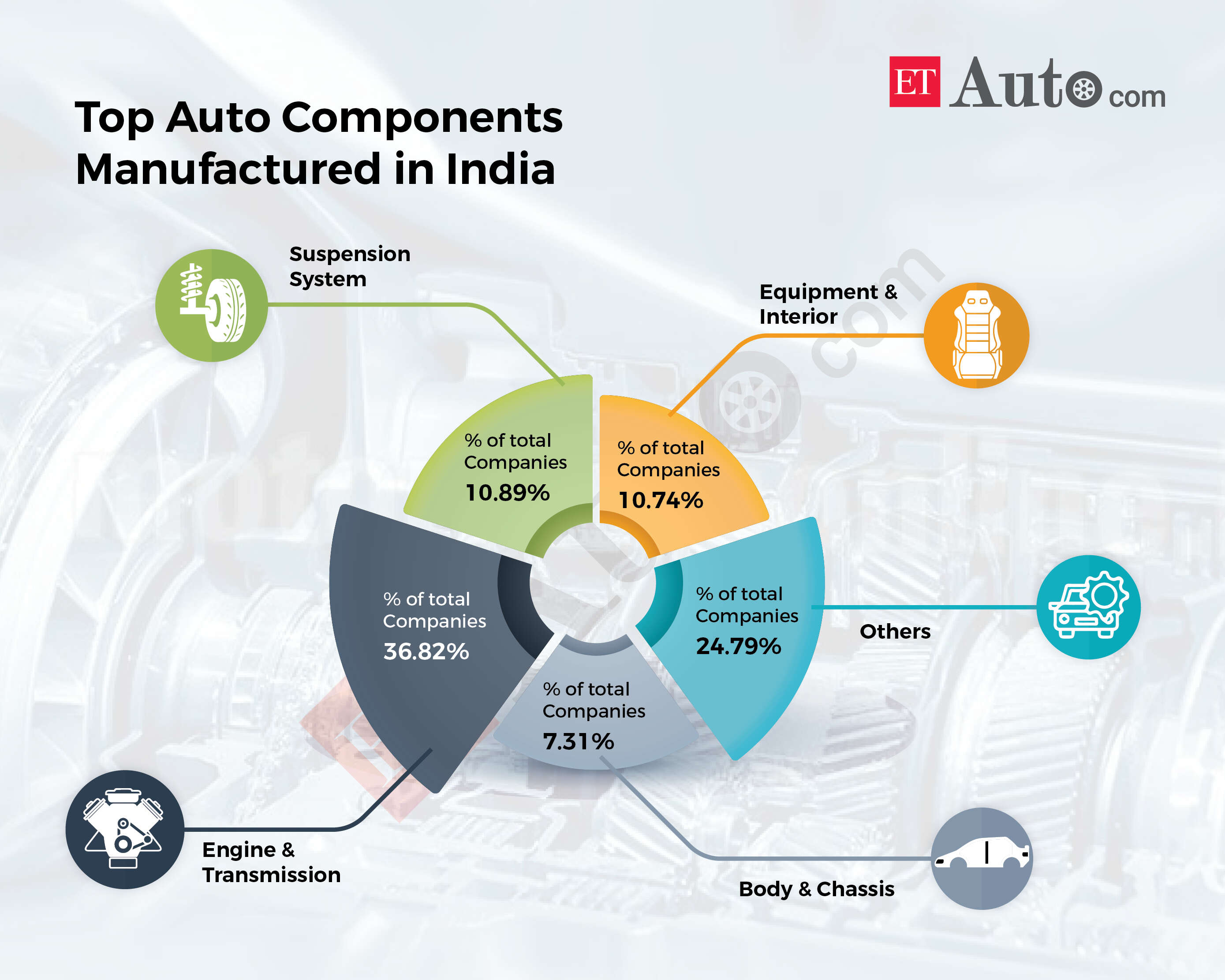

In the current scenario, the dependence on foreign JV partners is higher in case of electrical and electronics, a segment where 9 percent of the component makers in India work. Engine and transmission, which constitutes 37 percent of the total auto-parts makers in India, is another area where JVs and technical alliances are pivotal. In metal working, forging and casting and precision components, Indian-owned components tend to operate independently.

“With the growing adoption of connected, autonomous, shared and electrified mobility, the market share of foreign-owned (firms) or JVs with international technical partners will grow. In most cases, the royalty charges may range from 3-5 percent of revenue, depending on the nature of the technology transferred,” PwC partner-automotive Kavan Mukhtiyar told ETAuto.

New Techs, Higher Cost

The number of JVs and technical alliances involving transfer of new technologies has gone up in the past two years. The Uno Minda Group has signed three JVs — one each in advanced driver-assistance systems, electronics and wheel assembly — and one TA. Companies like Lumax Auto and Sandhar Technologies have got into alliances with foreign partners in the electronics and telematics space.

The dependence on foreign JV partners is higher in the case of electrical and electronics, a segment where 9 percent of the component makers in India work.~

Our analysis shows that 47-50 percent of the component industry’s total revenue is taken away by foreign-owned entities after excluding share of Indian partners in JVs. The cash outgo in these cases includes royalty, share of joint venture partners or payment to foreign parents of local companies.

Venkatram Mamillapalle, the Renault India managing director who had previously worked about three decades in supply chain and the auto-component industry, said other than the convenience of adapting to the changing technology faster, low volume in some high-cost technology had also made the industry opt for joint ventures or technical alliances.

“Like in the case of PCBs and chips you have the capability to develop it, but we don’t have volume. So, it’s better economic sense to import rather than design and develop locally. Globally, the spend on R&D is about 3-5 percent in normal technology, while in some technology it goes up to 8-10 percent of revenue. Is India capable of this kind of investment, do we have that kind of margin and volumes,” asked Mamillapalle. “However, we are not far away; in the next 5-7 years India might head in this direction.”

The average profit after tax of Indian-owned companies has been the lowest, compared with foreign-owned firms and JVs, probably because of the impact of the royalty payments. In FY2018, it (PAT) was 6.8 percent, 5.6 percent and 4.8 percent for foreign, JV and domestic companies, respectively.

Local manufacturers also burn cash in getting raw materials. In FY2018, the average cost of raw materials (of net sales) for foreign and JV firms was 49.3 percent and 51 percent, compared with 55.5 percent in case of homegrown component makers.

47-50 percent of the component industry’s total revenue is taken away by foreign-owned entities after excluding the share of Indian partners in JVs.~

Nevertheless, India’s entrepreneurial aspirations are unbridled. That has come true for the auto-component industry, too. The Motherson Group, with $11.7 billion revenue, has earned the reputation as a global company. The wiring harness major has 33 joint ventures, and it has acquired technology also through at least 22 acquisitions, mostly in Europe. Companies like Varroc and Rico have adopted the acquisition strategy to gain technology.

Demand for Royalty Cap

With the increasing trend of connected, autonomous, shared and electrified mobility, the automotive industry is in for the biggest transformation globally. In India, the change has been quite fast due to other reasons as well, largely policy-driven involving new safety and emission standards.

These changes have put the industry on its toes. Like always, the local industry is looking at overseas partners to bring in the emerging technologies. But homegrown companies are also concerned about the likely need to pay higher royalties. They are lobbying for bringing back royalty and technical fee restrictions. India had removed the royalty limits of 4 percent for domestic sales and 7 percent for exports till 2009.

While experts say free-trade agreements would make it difficult to tinker with such policies, the government seems to be exploring its options. Recently, the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion reportedly said it was working to revive limits on royalty payments. The payout for intellectual property is equivalent to 20% of foreign direct investment into the country, according to a report.